CHAPTER III

ON THE LONE BUSH TRACK

“Far, far off the daybreak calls hark! how loud and clear

I hear it wind !

Swift to the head of the army ! Swift ! spring to your places,

Pioneers ! O Pioneers ! ”

Walt Whitman.

WITH characteristic ingenuity and activity, Bishop Selwyn reached his destination rather more than three weeks before the ship on which he set sail. A voyage from Plymouth to Auckland was, in those days, a tedious ordeal for even the most lethargic passenger ; but, with the Bishop’s restless impatience to get to work, it was simply intolerable. Many of us, in this twentieth century of ours, have raced to and fro between England and New Zealand, completing the long journey, on our palatial ocean liners, in five or six weeks. But seventy years ago the good ship Tomatin took six months to reach her haven. She left Plymouth Sound, as we have seen, in December, 1841, and she cast anchor in Auckland harbour on 24th June, 1842. She had, however, reached Sydney on I4th April; but in moving up to her anchorage in that port she had unfortunately taken the ground, with the result that she was doomed to remain idle for some time, undergoing repairs. The Bishop, in strolling about the busy wharves, discovered a small brig the Bristolian about to sail for Auckland. He therefore decided to leave Mrs, Selwyn and some members of his party to come on by the Tomatin, whilst he and others transhipped to the Bristolian. In this way he contrived to land in New Zealand nearly a month before the Tomatin was sighted off the coast.

But we should make a grave mistake if we supposed that those months, spent in the motionless calm of tropical seas, or in tumbling through tumultuous gales about the Cape, were wasted in indolence. In the first place, the party was a large one, and could easily provide itself with abundant avenues of profitable entertainment. It included, besides the Bishop, Mrs. Selwyn and her baby boy, the Rev. C. L. Reay, of C.M.S., together with four clergymen (Messrs. Cotton, Whytehead, Cole, and Dudley), three catechists (Messrs. Butt, Evans, and Nihill), and a schoolmaster and mistress, all of whom the funds placed at the Bishop’s disposal by S.P.G. enabled him to take with him. The Rev. B. L. Watson also was travelling on the Tomatin, bound for Australia.

Dr. Selwyn’s alert mind, always hungry for information, and quick to scent even the most unpromising sources from which it might be obtained, swiftly discovered the means of acquiring proficiency in two arts, which proved simply invaluable to him on his arrival in New Zealand. And he applied himself to their mastery with such diligence and success that, when at last the Tomatin dropped her anchor, the Bishop could speak the Maori language with almost faultless fluency, and was a perfect expert in the science of navigation. The latter he had, of course, gathered from his intercourse with the captain of the ship. And, for the former, he had found a capable instructor in young Rupai, a Maori lad, who, by a fortunate providence, happened to be a passenger by the same vessel. The Bishop sought him out, gleaned from him the Maori word for this object and for that action, reduced his answers to a system, and at length found himself able to hold prolonged conversations with his young instructor in the native tongue.

When the Tomatin, after her long voyage, was pushing her way up the harbour at Sydney, a number of Maoris passed in a small boat under the bow of the vessel. Their astonishment may be imagined when the Bishop leaned over the bulwarks of the ship and shouted his greetings to them in their own language. It was on a glorious moonlight night that the Bishop, standing on the deck of the Bristolian, caught the first glimpse of his diocese. Just before midnight, on Friday, 27th May, the “Three Kings” displayed their rocky headlands against the horizon. The spectacle greatly impressed him. “God grant,” he wrote in his diary, “that I may never depart from the resolutions which I then formed, but by His grace be strengthened to devote myself more and more earnestly to the work to which He has called me!” At daybreak next morning the mainland of the North Island his future home stood out boldly on the skyline. At midnight, on Sunday, the moon again transfiguring both sea and land, the Bristolian cast her anchor at the mouth of Auckland’s beautiful harbour. “Every outward circumstance,” says the Bishop, “agreed with our inward feelings of thankfulness and joy.” As soon as the first faint streaks of daybreak appeared in the eastern sky, the Bishop was astir. In a few moments a boat, which he had purchased in Sydney, was lowered from the brig, and, plying his oars with a will, the Bishop had the satisfaction, before sunrise, of planting his feet on New Zealand shores. His chaplain, Mr. Cotton, bore him company in that early morning expedition, and was afterwards fond of telling how the Bishop, overcome by his emotions, threw himself upon his knees on the sand, and, in the grey light of the dawn, gave thanks to God for his safe arrival.

The newcomers lost no time in making their way to the house of Mr. Chief Justice Martin. The good man was not yet up, but he was soon dragged from his bed, and constrained, together with the Attorney-General, Mr. Swainson, to row back to breakfast on board. Afterwards, Dr. Selwyn called at Government House, to pay his respects to Captain Hobson, who showed him the most cordial hospitality until some permanent arrangement could be made. When the Governor had received intelligence from England that a bishop was about to be appointed to New Zealand, he flung down the dispatches in amazement, and exclaimed: “A bishop! What on earth can a bishop do in New Zealand where there are no roads for his coach?” But when he beheld the recipient of the surprising appointment he changed his mind. “Ah !” he remarked, “that is a very different thing: this is the right man for the post!”

On his first Sunday in the new land the Bishop threw the Maoris into ecstasies of delight by gathering them together and briefly addressing them in their own language. They were filled with unbounded astonishment at the advent of the white preacher, who could so fluently discourse to them in their native tongue. There can be no doubt that, by this single achievement, the Bishop completely disarmed their prejudices and favourably inclined their minds to welcome his message. It was a master-stroke. On the same day he addressed himself in English to the settlers and the members of his own party. One or two sentences from this “Thanksgiving Sermon” betray the thoughts that were surging in his mind. “A great change,” he said, “has taken place in the circumstances of our natural life; but no change which need affect our spiritual being. We have come to a land where not so much as a tree resembles those of our native country. All visible things are new and strange; but the things that are unseen remain the same. The same Spirit guides and teaches us. The same Church acknowledges us as her members; stretches out her arms to receive and bless our children, to lay her hands upon the heads of our youth, to break and bless the bread of the Eucharist, and to lay our dead in the grave in peace.” His text on that historic occasion was marked by that striking appropriateness which always distinguished his Scriptural quotations: “If I take the wings of the morning, and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there shall Thy hand lead me, and Thy right hand shall hold me.”

Let us glance around at this rude and primitive civilisation into the midst of which we have so suddenly plunged. Our references to Government House, and to the presence of a Chief Justice and an Attorney-General, may create a distinctly false impression. There, then, is the residence of His Excellency, a hurriedly constructed one-storied wooden cottage! Round about it huddle a few even less pretentious structures. About fifty soldiers are housed in a wooden barracks over yonder. Here is the rough old Court House, which also does duty as a church. This track, leading down into the township, will take us to a tiny cluster of stores. There are as yet no roads. The bush is everywhere, and as one looks down from the hill, the insignificant group of modest dwellings, which, at this distance, look like mere dolls-houses, are lost in the wild and picturesque confusion of foliage with which, for centuries, Nature has decked and draped the entire landscape.

Having, in the course of a week or so, thoroughly acquainted himself with the immediate vicinity, the Bishop was impatient to explore the country a little farther afield. It was quite to his taste, therefore, when Governor Hobson informed him that he was about to despatch a representative to inquire into a Maori massacre which had just occurred in the Thames Valley, and invited him to join the expedition. As the schooner made her way along the coast, the Bishop was entranced at the exquisite beauty of the scenery which unfolded itself in panoramic splendour in every direction.

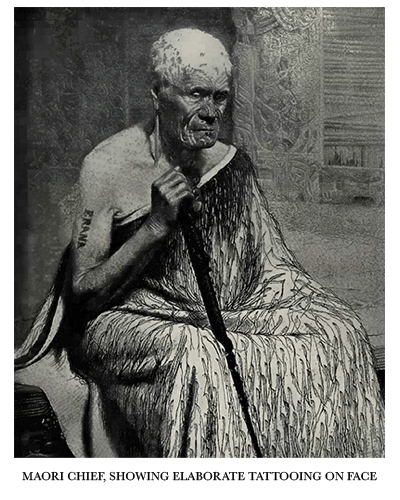

It was with infinite delight, too, that he cultivated that acquaintance with the native people which he had made, under such happy auspices, on his first arrival. Their manner of grouping themselves in villages or pas, together with all their domestic arrangements, simply captivated him. His introduction to a Maori pa was an experience which he was never likely to forget. He found the ordinary native families living for the most part in whares. A whare is a strongly constructed hut, ornately carved and elaborately adorned, thatched with raupo, and carpeted with mats of native flax. Here and there several families had established their domestic economy upon socialistic or co-operative principles, all living together in a whare puni, or larger whare. The advantage of this system was most pronounced in winter, when all slept together round the wall, with their feet towards the centre of the floor, where a great fire was kept blazing all through the night. Whenever it became necessary to hold a general deliberation, one of these apartments was transformed, for the time being, into a kind of Town Hall, and within its precincts the villagers assembled to discuss their grievances. The chiefs lived in larger and more imposing structures. But none of these native dwellings were to be despised. Although, in the nature of the case, the architecture was but rudimentary, and the execution primitive, the buildings were erected with considerable skill, and were wonderfully neat, weather-proof, and comfortable. The whole group of whares, whare-punis, and patakas (or storehouses) was surrounded by a high palisade, from behind the protection of which the villagers could resist a hostile visitation from a neighbouring tribe. These fortifications were constructed on so staunch a pattern, and on such excellent military principles, that, in the tragic days of the New Zealand war, the Maoris were often able to entrench themselves behind these palisades, and for days at a time hold our trained regiments at bay. The whole village, with its dwellings, store-houses, and fortifications, is called a pa ; and as the Bishop scrutinised its details for the first time, chatting the while with his native escort, with quiet dignity and easy grace he made no attempt to disguise his intense admiration of all that he saw. Moreover, he found occasion, in the course of his short tour, to admire the evidence of their integrity as well as the monuments of their industry, for he discovered that the houses of the settlers, living in close proximity to the pas, had not so much as a bolt upon the doors. Surrounded by natives, the property of the white man was inviolable.

They found at last the old chief who had been mainly responsible for the recent massacre. He sat in solemn state, wrapped in his blanket, and surrounded by his tribe. After a long palaver he agreed, with manifest reluctance, to give up the slaves with which he had enriched himself in the late disturbance, and to behave himself peaceably in days to come. Having thus satisfactorily adjusted the matter, the party set out on their return to Auckland. They were unavoidably detained, over the Sunday, at a settlement about twelve miles from headquarters, and the Bishop turned the delay to the best account by conducting service in the native language. They reached Auckland next day, having been absent five days.

One other journey of importance the Bishop made whilst waiting for his wife’s arrival. After having carefully studied a map of the country, and taken counsel with the Government officials at Auckland, he came to the conclusion that he ought to make his permanent home at a village on the Bay of Islands, at which the Church Missionary Society had already established its principal station. And as it was within the blue waters of this bay that the Tomatin was expected to first cast anchor, the most powerful incentives combined in pointing the Bishop northwards. Immediately on his return from his first jaunt, therefore, he again set sail, and losing no time on the voyage, safely reached the mission-station. We shall allow the good missionary’s wife to tell the story of his arrival. Writing to a friend in England, she says:

“Our good Bishop has arrived! He took us all by surprise. He had been becalmed off the heads, took to his boat, and reached this place soon after dark. W. and H. were soon down at the beach, where they found the head of our New Zealand Church busily engaged in assisting to pull up the boat out of the surf. Such an entree bespoke a man fit for a New Zealand life. We are all delighted with him; he seems so desirous of doing good to the natives, and so full of plans for the welfare of all.”

The Bishop had scarcely settled down to prepare his future home, and make general arrangements for the establishment of his headquarters at this spot, when a messenger rushed to him with the welcome intelligence that the Tomatin was lying at anchor in the offing. To continue the letter from which we have just quoted, the missionary’s wife goes on to say :

“The Tomatin has arrived, bringing Mrs. Selwyn and the rest of his numerous party.

We admired him before, but he has completely won our hearts to-day by his reception of his wife and family.”

It was about ten miles from the landing-place to the mission-station at Waimate, and in those days the task of conducting the party, and its necessary baggage, even that moderate distance was attended by no small difficulty. At length, however, the settlement was reached. The house of a Mr. Clarke had been secured as a “Bishopscourt” for the present ; and it was arranged that Mrs. Selwyn should consider herself a guest at the mission-house until the episcopal dwelling had been put into thorough repair. The Waimate was, at that period, the most settled district in New Zealand ; and here, to a greater extent than anywhere else, the influence of the missionaries had made itself felt. The Lord’s Table was frequently surrounded by as many as four hundred native converts. Its very remoteness from the centres, into which the flowing tide of immigration was beginning to pour, commended it to the Bishop in selecting a home. He knew that he himself would be absent for long periods on his evangelistic labours; and he felt an intense horror at the thought of leaving his loved ones to breathe the unwholesome moral atmosphere that too often characterises new colonial settlements. Mrs. Selwyn quickly fell in love with her new surroundings and associates. The Waimate itself, with its cosy houses and pretty gardens clustering around the white spire of the little church, reminded her of an English village. She would often take her little boy and stroll away along the tracks into the bush, and return to the mission-house delighted with the new ferns and mosses which she had gathered in her ramble. The Maoris themselves, too, were a source of perennial interest to her. She was especially amused at their culinary arrangements, and loved to see them cook their food. She watched them dig an oven a circular hole two or three feet wide out of the ground. In this pit a large fire was kindled; a layer of stones was laid upon the blazing pile; and, as the wood crumbled to ashes, these stones, giving off a fierce heat, fell to the bottom of the excavation. The wood was then shovelled out; the stones, by means of a stout stick, were arranged evenly in rows and covered with a layer of green leaves; on these the food was then placed. Another layer of leaves covered it, and the earth was then restored until the hole was almost filled again. After a time the oven would be reopened, and the food, “done to a turn,” was taken out and eaten.

One grievous disappointment cast its gloom over their first home at the Antipodes. Dr. Selwyn’s old friend and chaplain, the Rev. T. B. Whytehead, from whose magnetic influence over young men in England the Bishop had been led to anticipate great things in the coming days, was too ill when the Tomatin left Sydney to resume the voyage. And when, subsequently, he did complete the journey and rejoin the party, he only asked of the new land a grave.

But the time had now come to start work in real earnest, and the Bishop, having seen his wife and child comfortably ensconced in their cosy quarters at the Waimate, began to apply his restless mind to a plan for compassing the needs of his enormous episcopate. He determined to spend the remainder of the year 1842 in a personal visitation of the whole of the North Island, and to follow up this stupendous programme by a southern tour in 1843. When we remember that, as the crow flies, a thousand miles intervene between the North Cape and the Bluff; when we reflect, too, that it was the Bishop’s intention, not simply to travel through the land from Dan to Beersheba, but to zigzag from settlement to settlement, acquainting himself with all the people of his huge diocese; and when we further remind ourselves that, necessarily, much of the ground must be covered on foot, we can form a vague notion of the colossal proportions of his undertaking. On 28th July, five weeks after his wife’s arrival, he set out upon his first great expedition. He returned on 9th January of the following year, having traversed in the interval 2685 miles, of which 1400 were by ship, 397 by boat, 126 on horseback, and 762 on foot!

The best descriptions of these long feats of endurance and exploration are contained in his letters to his father. They were great days, in the dear old home, when letters arrived from over the seas. And such letters! For they consisted, not merely of pages and pages of racily written descriptions of his wild nomadic life, lit up by vivid and realistic flashes which seemed to bring New Zealand next door to Great Britain, but also of exceedingly clever pen-and ink sketches of every scene and object that called for particular attention. Dr. Selwyn put his very best into his home letters. They were literary gems and artistic masterpieces. They were, moreover, couched in terms of the old-time boyish frankness ; and breathed, in every stroke of the pen, that fragrant atmosphere of transparent devotion and undying affection in which, in the heart of their writer, every thought of home was immutably enshrined.

It is from these tender and characteristic epistles, which filled at the same time the eyes of their readers with tears, and their hearts with grateful pride, that we gather the most authentic impressions of these wonderful and adventurous pilgrimages. On, and ever on, he tramped along the tortuous bush tracks, mile after mile and day after day. The very tuis and bell-birds must have come to know that lithe and lonely figure as he invaded their sylvan solitudes, and, pausing not nor resting, pressed tirelessly on. It was in prosecuting these great tours that his cross-country work at Eton proved invaluable to him. No obstacles turned him aside. He found a way or made it. He negotiated the most broken and forbidding country with a facility which would have kindled the envy of a royal engineer. In every gully and ravine he discovered a spot at which he could cross the mere, ford the stream, or splash his way through the lagoon. By the bank of the river he would either strip for a swim, or inflate his air-bed, and fastening it to boughs torn from the trees, convert it into a magnificent raft. It was a part of his creed, and a part to which he clung as tenaciously as to any, that difficulties were designed for the express purpose of being overcome. He laughed his way through obstacles that to most men would have been insuperable. Sometimes he was attended in these long marches by admiring and devoted natives. Occasionally one of his colleagues went with him ; and once or twice his great friend, Mr. Chief Justice Martin, was able to dovetail his own itinerary into the programme of the Bishop. But often he was quite alone, pitching his little camp at night beside a giant kauri or beneath some spreading native beech, and at the first suspicion of sunrise, folding his tent like the Arab, and silently stealing away.

Captain Jacobs, of the Mission schooner Southern Cross, once overtook the Bishop travelling north, riding one horse and leading another ; the latter bore the impedimenta of his camp. The captain, who was about to enjoy the hospitality of a neighbouring settler, invited the Bishop to share the kindly accommodation with him. The well-meant offer was instantly and firmly declined. “You see,” he said, “people get up so late. By the time that they are having breakfast, I shall be half-way on my journey.” As it happened, however, Mr. Jacobs had not travelled many miles next morning before he came upon the Bishop sitting gipsy-like in front of a fire by the side of the track, in the blaze of which he was evidently cooking his breakfast. He explained that his fond hopes of an early start had been cruelly frustrated by the horses having broken away during the night. On the opposite side of the crackling flames, obviously on the best terms with his ecclesiastical companion, squatted the most worthless-looking tramp that it was possible to see. “He positively hadn’t five shillings worth of clothes on him!” Captain Jacobs would exclaim, in telling the story. “You see,” said the Bishop, with an inclination of his head towards his strange guest, “I have a friend to breakfast!” “Ay,” the captain would add in relating the incident, “and he meant it too!”

This al fresco hospitality was a common feature of these long bush marches. The Bishop hated to eat his morsel alone. Innumerable stories are told by his friends of the way in which they would find him on a track over the mountains, or in the shaded recesses of some thickly wooded valley, sharing his frugal meal with an aged Maori, or spreading a simple repast on the bark of a fallen tree for the entertainment of some fellow-traveller, who, by a mistaken reckoning, found himself at an unexpected distance from his base of supplies. And in every case he was on the best of terms with his companion. Whether listening to the prattle of a Maori child who had wandered from a neighbouring pa; or sharing his lunch with a bronzed and broad-shouldered squatter; or chatting with an awkward, loose-limbed lad from a remote settlement, he was always perfectly at his ease, and always imparting the same sense of freedom to his guest.

Nor were these continuous pilgrimages mere purposeless tramps. Whenever he caught sight of the wreathing column of smoke that betokened the settler’s hut, he instantly turned aside to acquaint himself with the people and their conditions. Whenever he came upon some rustic township, bush settlement or native pa, he at once pitched his tent, and threw all his energy into his ministration to the deepest needs of the people. He conducted services whenever, and wherever, he could find or make an opportunity, sometimes in a barn or loft, sometimes in a concert-hall or dancing-saloon, sometimes in a native whare, and often in the open air. The azure sky was frequently his cathedral dome, the bush- birds his choristers. The most unaffected and approachable of men, he induced alike the roughest and the shyest to entrust him with their confidences. He comforted the aged; he counselled the middle-aged; and young people and little children delighted in his company. Moreover, he was often called to “heal the sick” as well as to “preach the Gospel,” and with all a man’s strength, and all a woman’s gentleness, he executed this part of his apostolic commission. “What an admirable nurse he was!” wrote a lady friend, who had often witnessed his ministry to the stricken and the suffering. “There are many now living who can tell of his tenderness and patience in this capacity.”

The only person for whom the Bishop showed no consideration was himself. Mr. Abraham (afterwards Bishop of Wellington) tells how, in the course of a long walk from one end of the North Island to the other, the Bishop stopped, apparently to adjust a boot-lace, and told Mr. Abraham to go on, saying: “I will overtake you in a minute.” The delay lasted longer than he had expected, and Mr. Abraham strolled back to ascertain the cause. He found the Bishop treating an ugly and inflamed wound on his heel, and stolidly hacking away the proud flesh with his pocket-knife. In relation to the sufferings of others he was acutely sympathetic, but where he himself was concerned, he was a perfect Spartan.

On reaching Wellington, the southern limit of his first visitation, he was joined by the Chief Justice, who saw at a glance that this rude life of privation and endurance was already telling upon him. “As our boat neared the beach,” writes the Judge, “the Bishop stood there to welcome us. It was very joyous to meet him again, but I was struck by his pale, worn face. He was nursing the sick in the person of poor Evans, who had then been given over by the physicians. He was to all appearances sinking. The Bishop was watching and tending as a mother or wife might watch and tend. It was a most affecting sight. He practised every little art, that nourishment might be supplied to his patient. He pounded chicken into fine powder, that it might pass, in a liquid form, into his ulcerated mouth. He made jellies; he listened to every sound ; he sat up the whole night through by the bedside. In short, he did everything worthy of his noble nature. It went to my heart.” To the great grief of the Bishop the patient died, leaning, in his last anguish, upon the arm of his assiduous benefactor. “I had been with him three weeks,” the Bishop wrote to his mother, “and enjoyed much comfort in the simple manner in which he expressed the sincerity of his repentance, and the grounds of his hope for the life to come.” In a letter to Mrs. Martin, the Chief Justice tells how, in strolling over the sunlit hills next morning for a breath of fresh air before going into Court, he found there, amidst the life and beauty of a spring morning, a boy digging the grave of poor Evans. “The Bishop and I,” he adds, “have slept side by side, on two stretchers, in a huge loft ever since I came.”

His return journey led him through country more closely settled by immigrants on the one hand, and more thickly peopled by native tribes on the other. At Waikanae, more than five hundred Maoris crowded together to hear him; and as he addressed them in their own rhythmic and musical language, he was delighted to notice, from the quickly changing play of expression upon their countenances, that his utterance was followed with interest, and its deeper significance apprehended with ease. It was evident that, among the natives, his fame had preceded him. At every pa he was welcomed with boisterous enthusiasm, and tribe vied with tribe in demonstrating its delight. Here, enormous bonfires blazed in honour of his approach; whilst there, animals were slaughtered and presented as a token of goodwill. Sometimes, indeed, these effusive manifestations of rejoicing at the coming of the great white preacher stood in imminent peril of appearing somewhat ludicrous. On one occasion, for example, he visited a strong and fortified pa which had recently made its name notorious in connection with a most revolting massacre, followed by the supplementary horrors of cannibalism. The guilty people received the Bishop with the most frenzied delight, the principal murderer being himself most assiduous in his attentions.

Having followed the coast-line as far as the point at which the waters of the beautiful Manawatu empty themselves into the sea, Dr. Selwyn decided to reorganise his party, in order to make the ascent of the stream. On 7th November, therefore, he found himself at the head of an expedition consisting of six canoes, each containing eight men, fully equipped for the long river journey. New Zealand has many claims upon the admiration of beholders, but in her river scenery she surpasses herself. The clear and tranquil waters, reflecting as in a mirror the majestic hills on either side, are at once the rapture of the poet and the despair of the artist. As far as eye can reach, in every direction, the mountainous peaks lift their massive heads to the skies, sometimes feathering gently and gradually down to the river’s brink, and sometimes falling with abrupt and precipitous suddenness to the water’s edge. As the canoes glide on, we catch glimpses of range beyond range, in bewildering number and variety, every slope densely clothed with a glorious tangle of magnificent bush, which, from the branches that wave triumphantly from the dizzy heights above, to those that lean over and bathe their verdure in the eddies of the stream, nowhere knows a break.

Before the procession of canoes was launched upon its long expedition, the Bishop had received from Wellington a budget of letters and newspapers from home. Only those who have been similarly circumstanced can know the thrill that accompanies the arrival of the English mail. Yet so transcendently beautiful was the scenery, and so charming the foliage amidst which his little fleet was so gracefully moving, that the Bishop found it difficult to withdraw his gaze for a moment from the loveliness around him, in order to devour the precious contents of his welcome missives. Day after day the great flowering shrubs which, in all their early summer glory, imparted to the evergreen bush a magnificent profusion of colour, the rhythmic plash of the paddles in the silvery waters, and the wild melody of the myriad songsters in the forest around, wove themselves into a memory of music and delight which haunted the Bishop to his dying day. The laughter of these waterfalls, the thunder of these cataracts, and the innumerable calls and echoes of the bush were with him even in his last hours. Night after night, when the mopoke was shouting his strange cry down the wooded valleys, the party would paddle ashore and pitch their encampment. At every sign of a settlement, progress was instantly suspended, greetings exchanged, and a service conducted. When Sunday dawned, they were far from any traces of population. It was a glorious day, sunny but not sultry. The Bishop gathered his Maori attendants together, and in his own homely and felicitous style expounded to them the eternal message of the love of Christ. Later in the day he indulged in a restful stroll through the charming environs of the camp. And before retiring for the night, he once more assembled his party, and committed them to that Divine care, beyond which, by peak or by plain, by sea or by shore, none who trust can ever drift.

The next day afforded them the opportunity of enjoying the more exciting pleasures of the chase. They forsook the river and struck inland towards the east coast. After some little exploration they came upon a noble plain, across which they were able to walk for eighteen miles on soft, fresh grass. The district abounded in wild pigs, and when at night the hunters turned towards the camp, each man was heavily laden with his porcine spoil. In this vicinity, too, they discovered a fine lake, in the centre of which stood a small island, on which a native settlement had been erected. In response to their signals, the Maoris sent canoes across the rippling waters to bring the episcopal party to the pa. Wrapped in his flowing blanket, the chief pronounced an oration of welcome, “with all the dignity” to quote Dr. Selwyn’s words “of a Roman senator.” But when, he adds, “the time came for our departure, he prepared to accompany us by dressing himself in a complete English suit of white jean, with white cotton stockings, shoes, neckcloth, and shirt complete. His wife was dressed in a brilliant cotton gown, spotted with bright red, and a good English bonnet, but without shoes or stockings. The canoe, being in shallow water, some distance from the shore, the dutiful wife saved her husband’s shoes and stockings by carrying him on her back to the boat.”

On November 6th an awkward predicament overtook them. After conducting a service at Ahuriri, they found the canoe stuck fast, and the tents out of reach! At length one tent was procured, in which the first Bishop of New Zealand, the first Chief Justice, and the first Archdeacon huddled together for the night. “Surely,” writes the Bishop, “such an aggregate of legal and clerical dignity was never before collected under one piece of canva!”

It was amidst such alternating scenes of gravity and gaiety that this long and memorable tour of episcopal visitation drew to its close. Sometimes we see the Bishop preaching with great force and fervour to as many as a thousand Maoris at once, they standing bare-headed beneath the scorching summer sun, whilst he addresses them from beneath the canvas awning which they have erected for his accommodation. Sometimes we catch a glimpse of him bending over the prostrate form of a member of his staff, who, overcome by the heat and excitement of the journey, has developed a malady which sorely taxes all his master’s ingenuity and resource. And at other times we see him crossing a river, either by felling a tree to serve as a rustic bridge, by swimming, if not encumbered by heavy baggage, or by punting across on a hastily improvised raft.

He had fondly hoped to be back at the Waimate in time to spend his first midsummer Christmas with his wife and child. But all hope of realising this alluring dream had to be reluctantly and ruthlessly abandoned. It was getting towards the end of November when, emerging from the bush-land of the interior, they heard the roar of the breakers on the east coast of the island. On 20th December he slept in a potato-field, which, as he said, possessed the twofold advantage of providing him with both bed and board. The next day he saw the steam rising from the thermal district of Rotorua. A few hours later he reached the banks of the Thames, and contrasted that lonely stream with the busy river around which most of his Eton and Windsor recollections centred. Christmas Day was spent in conference with an old chief who, whilst really heathen, made a profession of Roman Catholicism in order to evade the attentions of Protestant missionaries. On Sunday, January 1st, he “reviewed with great thankfulness the events of the past year, so full of new and important features”; and on January 3rd he reached Auckland. His own record of his return is too striking to be omitted.

“On Tuesday, January 3rd,” he says, “my last pair of thick shoes being worn out, and my feet much blistered by walking on the stumps, I borrowed a horse from the native teacher and started at 4 A.M. to go twelve miles to Mr. Hamlin’s Mission Station, on Manakau harbour. Then ten miles by boat across the harbour. It is a noble sheet of water, but very dangerous from shoals and squalls. After a beautiful run of two hours I landed with my faithful Maori, Rota, who had steadily accompanied me all the way, carrying my bag with gown and cassock the only articles in my possession which would have fetched sixpence in the Auckland rag-market. My last remaining pair of shoes (pumps) were strong enough for the light and sandy walk of six miles to Auckland ; and at 2 P.M. I reached the Judge’s house by a path, avoiding the town, and passing over land which I have bought for the site of a cathedral. It is a spot which, I hope, may hereafter be traversed by many bishops better shod, and far less ragged, than myself.”

If, in addition to his longing to see his dear ones, any other incentive were needed to hasten his steps towards the Waimate, it was supplied by the news which greeted him on his entrance into Auckland, of the arrival, in a most critical condition, of his friend, the Rev. T. B. Whytehead. Only those who had walked, as closely as the Bishop had done, with this choice and cultured spirit, could appreciate his worth. It was a fundamental part of Dr. Selwyn’s programme to establish a College at Waimate with Mr. Whytehead as its principal. Without losing an hour, therefore, he hurried on. When approaching the settlement, Mr. Whytehead was one of the first to greet him, “his pale and spectral face telling its own story.” A day or two later the invalid took to his bed. Each evening the Maori Christians, to whom he had ministered, ranged themselves beneath his window, and sang, in their own language, “Glory to Thee, my God, this night!” a hymn which Mr. Whytehead had himself translated for them. Ten days after his chiefs return, the patient sufferer passed peacefully away ; and the Bishop felt that his burial gave to the and of his adoption a new sanctity and an added claim. Perhaps the most eloquent tribute ever paid to this good man’s memory was offered when, twenty-five years later, the members of St. John’s College, Cambridge, erected a new chapel. They engraved the name of Thomas Whytehead on the vaulted roof, side by side with those of Henry Martyn, William Wilberforce, William Wordsworth, and James Wood, as the five most distinguished benefactors of their race which the College, during the nineteenth century, had produced.

But meanwhile the Bishop was at home again ! After his prodigious labours and ceaseless privations, he was permitted to breathe a softer atmosphere. His delight at finding his wife and child in excellent health, and in once more revelling in the luxury of their society, knew no bounds. The missionaries and their families welcomed him back with a will. The Maoris, on catching sight of him, clapped their hands and shouted “Haere Mail” (Welcome!). And the whole settlement assumed a festal air on his return.

0 Comments