II

WULLIE

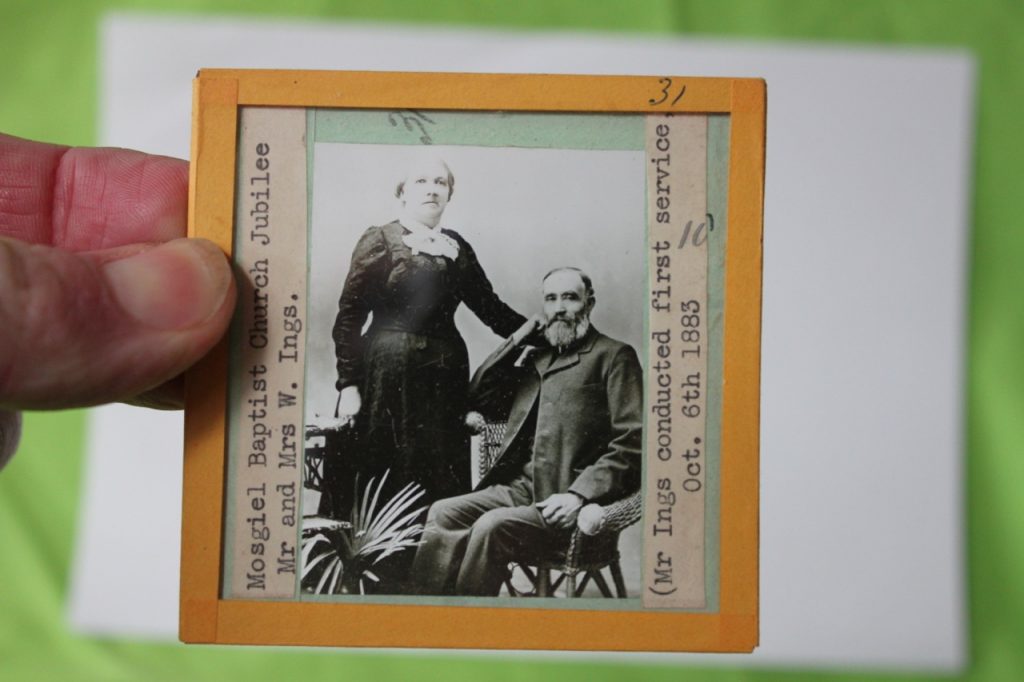

Wullie was my first deacon. That is to say, he was the senior deacon of my church in Maoriland when I arrived. It was a great and memorable night in my life when I met him first. I had been asked by the college authorities to go out to New Zealand and be the first minister of the church at Mosgiel. I consented with a light heart. But the long, long voyage had opened my eyes to the enormous chasm that yawned between me and all that I really loved. Here was I, a stranger in a strange land, an exile in the uttermost ends of the earth. And it was a very dejected and miserable and home-sick young minister who was being borne into Dunedin on the Christchurch express that night. It was the last stage of a journey that had seemed interminable. Or almost the last stage. For at Dunedin I was to change, and take the suburban train that was actually to land me in Mosgiel. I sat there in the express, trying to imagine the people who would presently meet me— the people who were to be father and mother and brothers and sisters to me through the long years to come. A few names had reached me, and I attempted to conjure up forms and faces to fit them. It is never a very satisfactory business, and I was not sorry when the twinkling lights of the city and the wild scream of the engine announced that we were approaching Dunedin at last.

I suspected that some of my new people might be lying in wait for me here, and I was not mistaken. As the train slowed into the brightly-lit platform, I caught a glimpse of a group of eager and inquisitive faces anxiously scanning every carriage. I was soon in the midst of them, receiving a most gracious welcome. They were all kindly and reassuring; but of all those honest and homely faces one stood out from among the rest. It was one of the simplest, and yet one of the saintliest, faces I have ever seen. What ruggedness was there ! And yet it was luminous, for it fairly shone! It was a winsome face, and mischief twinkled in those eyes. It belonged to an elderly little Scotsman. My dejection thawed beneath his smile. All loneliness vanished. In some occult way of his own he made me feel that I was trusted and honoured already. His wrinkled face beamed; his bright eyes sparkled; and his speech faltered through deep emotion. Lookers-on might have been pardoned for supposing that I was his son. I had dreaded that night’s experience as the greatest ordeal of my life. He dispelled the illusion and turned it into a home-coming. I was among my own people. One man at least loved me, and that man was Wullie. ‘Puir laddie!’ he said, as he reflected on my long voyage to a strange folk.

I have said that I was the first minister at Mosgiel. That is scarcely true. Wullie was the first minister. He was the father of them all. It was a very well-worn track that led to Wullie’s door. The young people confided their love affairs to Wullie; the older people poured all their troubles into his sympathetic ear. He was pastor and peacemaker. I always think of Wullie when I recall that great saying in Ecce Homo: ‘The truth is that there has; scarcely been a town in any Christian country since the time of Christ where a century has passed without exhibiting a character of such elevation that his mere presence has shamed the bad and made the good better, and has been felt at times like the presence of God Himself. And if this be so, has Christ failed? or can Christianity die?’ No; Christianity is safe as long as there are men like Wullie about.

And yet I was the first minister after all. I learned afterwards how Wullie had set his heart on having a minister at the church. He had thought about it, talked about it, and prayed about it until it had become the one fond dream of his old age. At every church meeting he rose and wistfully referred to it. Were the members quite sure that the time was not yet ripe? And when at last, with great trepidation, the church yielded to his importunity, and committed itself to the formidable proposal, Wullie’s delight broke all bounds. How impatiently he had awaited the letter from the English college! How excitedly he had spread the great news that a minister was actually coming! How he had pored day by day over the shipping news for any fragmentary tidings of the vessel that bore me! I could understand all this afterwards in the light of the welcome he gave me.

Four months later, on Wullie’s motion, of course, the church decided to terminate the temporary character of my appointment and to call me to its permanent pastorate. On my acceptance the good people presented me with a cosy arm-chair. Wullie was appointed to make the presentation. He read his speech. He could not trust himself that night without manuscript. His heart was full. I shall never forget his tenderness and enthusiasm. I little dreamed that Wullie was addressing us all for the last time.

Nor was it quite the last time. For Wullie’s last speeches — if single sentences can properly be classified as speeches — were delivered at a church meeting. If I must enter into details of a distinctly domestic order, the church was in financial difficulties. I do not mean that they had not enough money. I mean that they had too much. The one overpowering dread of these cautious Scots folk had been lest they should lure a young minister all the way from England and then find themselves unable to support him. This horror had alone constrained them, through many years, to postpone the realization of Wullie’s darling dream. And when the minister was actually there, the fear became still more acute, with the result that the members contributed with frantic munificence. The exchequer was overflowing, and the poor treasurer was at his wit’s ends.

Nor was it quite the last time. For Wullie’s last speeches — if single sentences can properly be classified as speeches — were delivered at a church meeting. If I must enter into details of a distinctly domestic order, the church was in financial difficulties. I do not mean that they had not enough money. I mean that they had too much. The one overpowering dread of these cautious Scots folk had been lest they should lure a young minister all the way from England and then find themselves unable to support him. This horror had alone constrained them, through many years, to postpone the realization of Wullie’s darling dream. And when the minister was actually there, the fear became still more acute, with the result that the members contributed with frantic munificence. The exchequer was overflowing, and the poor treasurer was at his wit’s ends.

‘If the church get to know that we’ve got all this money,’ he exclaimed in despair, ‘the collections will drop off to nothing!’

This was at a deacons’ meeting. It was generally agreed that in some way or other the money must be spent, and each man undertook to try to think out the best means of disposing of it. But their plans were all shattered. At the church meeting held a few days later one of the members, little dreaming that he was precipitating a crisis, asked for a financial statement. The treasurer slowly rose. He was the picture of abject misery. Anguish was stamped upon his face. He could not have looked more forlorn or wobegone had he stood convicted of misappropriating the church funds. He confessed, with the countenance of a culprit, that he had fifty pounds in hand! The position was appalling!

But at that fateful moment WuHie, as his custom was, sprang into the breach and saved the situation. He rose deliberately, a sly twinkle in his eye, and quietly asked:

‘Would the meenister tell us if he has a lassie?’

I was covered with confusion, and I buried my face to hide my blushes. I confess that, for two minutes at least, I lost control of that meeting. But, happily, my very confusion saved me the necessity of a reply. My secret was out. Wullie was on his feet again.

‘Then, Mr. Chairman,’ he said, with the gravity of a statesman, ‘I move that we buy a piece of ground with that fifty pounds, and that we build the meenister a manse.’

The resolution was carried with enthusiasm. The treasurer looked like a man who had been saved from the very brink of destruction. The manse was built, and it was for many years my home. It had but one discomfort, and that was the sorrowful reflection that poor Wullie never lived to see either the manse or its mistress. One Saturday afternoon, as we were all preparing for an anniversary celebration on the Sunday, without a sickness or a struggle Wullie suddenly passed away. We were thunderstruck. It was incredible. I have rarely seen grief so general and so sincere.

Wullie had some queer little ways. Among his peculiarities was this : When he went to the pay office at the factory and drew his weekly wage, he always looked the coins carefully over with a keen and critical eye, and laid aside the bright ones for the church collection. ‘The Lord must aye hae the best, ye ken!’ he used to say. He could not bear to put a worn or battered coin upon the plate. At a crowded memorial service, at which the whole countryside turned out to do honour to his memory, there fell to me the heavy task of preaching Wullie’s funeral sermon. I referred to this habit of his with the coins. It was so eminently typical and characteristic. ‘If,’ I said, ‘I were asked to suggest a suitable epitaph to write above his grave, I should inscribe upon the stone these words: “Here Lies a Man Who Always Gave His Best in the Service of His Saviour!”’ And he who visits the pretty burying-place on the outskirts of Mosgiel at this day may easily find the green spot where Wullie sleeps, and read that faithful record engraved above his head.

F.W. Boreham, 1914.

![Navigating Strange Seas, Part 1, "ENGLAND" Navigating Strange Seas, Part 1, "ENGLAND" - Available to watch online as a rental or to buy digitally or as a DVD [more]](https://www.fwboreham.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/fwb-digital-download-part01.png)

![NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, Part 2 - "NEW ZEALAND" - Available to watch online as a rental or to buy digitally or as a DVD [more] NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, Part 2 - "NEW ZEALAND" - Available to watch online as a rental or to buy digitally or as a DVD [more]](https://www.fwboreham.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/fwb-digital-download-part02.png)

![NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, Part 3 - "HOBART" - Available to watch online as a rental or to buy digitally or as a DVD [more] NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, Part 3 - "HOBART" - Available to watch online as a rental or to buy digitally or as a DVD [more]](https://www.fwboreham.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/fwb-digital-download-part03.png)

![NAVIGATING STRANGE SEAS, Part 4 - "MELBOURNE" - Available to watch online as a rental or to buy digitally or as a DVD [more]](https://www.fwboreham.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/fwb-digital-download-part04.png)

0 Comments